Two Latin Plays

For High-School Students

A Roman School

90 B.C.

Drāmatis Persōnae

- Magister

- Servī

- Paedagōgus

- Aulus Licinius Archiās (iūdex)

- Pūblius Licinius Crassus (iūdex)

- Gāius Licinius Crassus (adulēscēns)

- Mārcus Tullius Cicerō (discipulus)

- Quīntus Tullius Cicerō (discipulus)

- Lūcius Sergius Catilīna (discipulus)

- Mārcus Antōnius (discipulus)

- Gāius Iūlius Caesar (discipulus)

- Appius Claudius Caecus (discipulus)

- Gnaeus Pompēius (discipulus)

- Pūblius Clōdius Pulcher (discipulus)

- Mārcus Iūnius Brūtus (discipulus)

- Quīntus Hortēnsius Hortalus (discipulus)

- Lūcius Licinius Lūcullus (discipulus)

- Gāius Claudius Mārcellus (discipulus)

- Mārcus Claudius Mārcellus (discipulus)

Scaena

When the curtain is drawn, plain wooden benches are seen arranged in order on the stage. Two boys stand at the blackboard, playing "odd or even"; two others are noisily playing nuces[1]; one is playing with a top, another is rolling a hoop, and a third is drawing a little toy cart. Three boys in the foreground are playing ball. They are Quintus Cicero, Marcus Cicero, and Marcus Antonius. With their conversation the scene begins.

Mihi pilam dā!

Ō, dā locum meliōribus!

Tū, Mārce, pilam nōn rēctē remittis. Oportet altius iacere.

Iam satis alta erit. Hanc excipe!

(Tosses the ball very high.)

(going up to Lucius Lucullus who has the cart) Mihi plōstellum dā.

Nōn, hōc plōstellum est meum. Sī tū plōstellum cupis, domum reversus inde pete.

Mihi tū nōn grātus es, Lūcī Lūculle.

(The Magister enters and loudly calls the roll, those present answering adsum.)

Mārcus Tullius Cicerō.

Quīntus Tullius Cicerō.

Lūcius Sergius Catilīna.

(Catilina is absent and all shout abest.)

Mārcus Antōnius.

Gāius Claudius Mārcellus.

Gāius Iūlius Caesar.

Appius Claudius Caecus.

(Appius is absent and all again shout abest.)

Lūcius Licinius Lūcullus.

Gnaeus Pompēius.

Pūblius Clōdius Pulcher.

Mārcus Iūnius Brūtus.

Quīntus Hortēnsius Hortalus.

Mārcus Claudius Mārcellus.

Nunc, puerī, percipite, quaesō, dīligenter, quae dīcam, et ea penitus animīs vestrīs mentibusque mandāte. Sine morā respondēte. (Writes on the board the sentence "Omnīs rēs dī regunt.") Nōmen dī, Mārce Cicerō, dēscrībe.

Dī est nōmen, est dēclīnātiōnis secundae, generis masculīnī, numerī plūrālis, cāsūs nōminātīvī, ex rēgulā prīmā, quae dīcit: Nōmen quod subiectum verbī est, in cāsū nōminātīvō pōnitur.

Bene, Mārce, bene! Ōlim eris tū māgnus vir, eris cōnsul, eris ōrātor clārissimus, quod tam dīligēns es. Quīnte Cicerō! (Enter Catilina late. He is accompanied by a paedagogus carrying a bag with tabellae.)

Ō puer piger, homō perditissimus eris. Quō usque tandem abūtēre, Catilīna, patientiā nostrā? Vāpulābis.

Ō magister, mihi parce, frūgī erō, frūgī erō.

Catilīna, mōre et exemplō populī Rōmānī, tibi nūllō modō parcere possum. Accēdite, servī! (Enter two servi, one of whom takes Catilina by the head, the other by the feet, while the magister pretends to flog him severely, and then resumes the lesson.[2]) Pergite, puerī. Quīnte Cicerō, verbum regunt dēscrībe.

(hesitatingly) Regunt est verbum. Est coniugātiōnis secundae, coniugātiōnis secundae, coniugātiōnis se...

Male, Quīnte. Tū es minus dīligēns frātre tuō Mārcō. Nescīs quantum mē hūius negōtī taedeat. Sī pēnsum crās nōn cōnfēceris, est mihi in animō ad tuum patrem scrībere. Haec nīl iocor. Tuam nēquitiam nōn diūtius feram, nōn patiar, nōn sinam.

Ō dī immortālēs, tālem āvertite cāsum et servāte piōs puerōs, quamquam pigrī sunt.

Quīnte Hortēnsī, verbum regunt dēscrībe.

Regunt est verbum; praesēns est regō; īnfīnītīvus, regere; perfectum, rēxī; supīnum, rēctum. Est coniugātiōnis tertiae, generis actīvī, modī indicātīvī.

Rēctē, rēctē, Quīnte! Bonus puer es. Gnaeī Pompēī, perge.

(crying) Nōn pergere possum.

Ō puer parve, pergere potes. Hanc placentam accipe. Iam perge.

(taking the little cake and eating it) Regunt temporis praesentis est; persōnae tertiae; numerī plūrālis nōmen sequēns, ex rēgulā secundā, quae dīcit: Verbum persōnam numerumque nōminis sequitur.

Rēctē! Nōnne tibi dīxī tē rem expōnere posse? Nihil agis, Gnaeī Pompēī, nihil mōlīris, nihil cōgitās, quod nōn ego nōn modo audiam, sed etiam videam plānēque sentiam. Gāī Mārcelle, tempus futūrum flecte.

Regam, regēs, reget, regēmus, regētis, regent.

Quae pars ōrātiōnis est omnīs, Gāī?

Omnīs est adiectīvum.

Rēctē; estne omnīs dēclīnābile an indēclīnābile, Pūblī Pulcher?

Omnīs est dēclīnābile, omnis, omne.

In quō cāsū est omnīs, Mārce Brūte?

Omnīs est cāsūs accūsātīvī ex rēgulā quae dīcit: Nōmen adiectīvum cāsum et genus nōminis substantīvī sequitur.

Cūius dēclīnātiōnis est omnīs, Mārce Mārcelle?

Omnīs est dēclīnātiōnis tertiae.

Potesne omnīs dēclīnāre?

Oppidō, magister, auscultā. (Declines omnis.)

Mārcus Claudius, suō mōre, optimē fēcit. Quam cōnstrūctiōnem habet rēs, Mārce Brūte?

Rēs est nōmen cāsūs accūsātīvī, quod obiectum verbī regunt est. (Enter Appius Caecus late. His paedagogus accompanies him.)

Magister, Appius Claudius hodiē māne aeger est, idcircō tardē venit. (Exit)

Poenās dā, "Micā, Micā," recitā.

-

- Micā, micā, parva stella,

- Mīror quaenam sīs, tam bella!

- Splendēns ēminus in illō

- Alba velut gemma caelō.

- Quandō fervēns Sōl discessit,

- Nec calōre prāta pāscit,

- Mox ostendis lūmen pūrum

- Micāns, micāns per obscūrum.

Quis alius recitāre potest?

(shouting) Ego possum, ego possum.

Bene; Mārce Antōnī, recitā.

-

- Trēs philosophī dē Tusculō

- Mare nāvigārunt vāsculō;

- Sī vās fuisset tūtius

- Tibi canerem diūtius.

(shouting) Mihi recitāre liceat.

Recitā, Gnaeī Pompēī.

-

- Iōannēs, Iōannēs, tībīcine nātus,

- Fūgit perniciter porcum fūrātus.

- Sed porcus vorātus, Iōannēs dēlātus,

- Et plōrāns per viās it fūr, flagellātus.

(holding up his hand) Novum carmen ego possum recitāre.

Et tū, Brūte! Perge!

-

- Gāius cum Gāiā in montem

- Veniunt ad hauriendum fontem;

- Gāius prōlāpsus frēgit frontem,

- Trāxit sēcum Gāiam īnsontem.[3]

Hōc satis est hodiē. Nunc, puerī, cor--Quid tibi vīs, Quīnte Hortēnsī? Facis ut tōtō corpore contremīscam.

(who has been shaking his hand persistently) Magister, ego novōs versūs prōnūntiāre possum. Soror mea eōs mē docuit.

Recitā celeriter.

-

- Iacōbulus Horner

- Sedēbat in corner

- Edēns Sāturnālicium pie;

- Īnseruit thumb,

- Extrāxit plum,

- Clāmāns, Quam ācer puer sum I.

Nunc, puerī, corpora exercēte. Ūnum, duo, tria.

(The discipuli now perform gymnastic exercises, following the example of the magister, who goes through the movements with them. These may be made very amusing, especially if the following movements are used: Arms sideways--stretch; heels--raise, knee bend; forehead--firm; right knee upward--bend.)

Cōnsīdite. Pēnsum crāstinum est pēnsum decimum. Cavēte nē hōc oblīvīscāminī. Pēnsum crāstinum est pēnsum decimum. Et porrō hunc versum discite: "Superanda omnis fortūna ferendō est."

(The magister repeats this verse emphatically several times in a loud and formal tone, the discipuli repeating it after him at the top of their voices.)

Iam geōgraphia nōbīs cōnsīderanda est et Galliae opera danda. Quid dē Galliā potes tū dīcere, Mārce Mārcelle?

Gallia est omnis dīvīsa in partēs trēs, quārum ūnam incolunt Belgae, aliam Aquītānī, tertiam quī ipsōrum linguā Celtae, nostrā Gallī appellantur.

Pūblī Pulcher, hōrum omnium, quī fortissimī sunt?

Hōrum omnium fortissimī sunt Belgae.

Mihi dīc cūr Belgae fortissimī sint.

Belgae fortissimī sunt proptereā quod ā cultū atque hūmānitāte Rōmae longissimē absunt, minimēque ad eōs mercātōrēs Rōmānī saepe commeant atque ea quae ad effēminandōs animōs pertinent, important.

Quis fīnēs Galliae dēsīgnāre potest?

(raising hands) Ego, ego possum.

Lūcī Lūculle, Galliae fīnēs dēsīgnā.

Gallia initium capit ā flūmine Rhodanō; continētur Garumnā flūmine, Ōceanō, fīnibus Belgārum; attingit flūmen Rhēnum ab Sēquanīs et Helvētiīs; vergit ad septentriōnēs.

Quōs deōs colunt Gallī, Gnaeī Pompēī?

Deōrum maximē Mercurium colunt; hunc omnium inventōrem artium ferunt, hunc viārum atque itinerum ducem esse arbitrantur. Post hunc Apollinem et Martem et Iovem et Minervam colunt.

Bene, Gnaeī. Quem deum, Catilīna, colunt Rōmānī maximē?

Nōs Iovem dīvum patrem atque hominum rēgem maximē colimus.

Nunc, puerī, cantāte. Quod carmen hodiē cantēmus? (Many hands are raised.) Gāī Caesar, quod carmen tū cantāre vīs?

Volō "Mīlitēs Chrīstiānī" cantāre.

Hōc pulcherrimum carmen cantēmus. (A knock is heard. Enter Publius Licinius Crassus and Aulus Licinius Archias with slaves carrying scrolls.) Salvēte, amīcī. Vōs advēnisse gaudeō. Nōnne adsīdētis ut puerōs cantāre audiātis?

Iam rēctē, carmen sānē audiāmus.

Optimē, puerī, cantēmus. Ūnum, duo, tria.

(All rise and sing; each has the song[4] before him on a scroll.)

-

- Mīlitēs Chrīstiānī,

- Bellō pergite;

- Cāram Iēsū crucem

- Vōs prōvehite.

- Chrīstus rēx, magister,

- Dūcit āgmina,

- Eius iam vēxillum

- It in proelia.

- Māgnum āgmen movet

- Deī ecclēsia.

- Gradimur sānctōrum,

- Frātrēs, sēmitā.

- Nōn dīvīsī sumus,

- Ūnus omnēs nōs;

- Ūnus spē, doctrīnā,

- Cāritāte nōs.

- Thronī atque rēgna Īnstābilia,

- Sed per Iēsum cōnstāns

- Stat ecclēsia.

- Portae nōn gehennae

- Illam vincere,

- Nec prōmissus Iēsū

- Potest fallere.

- Popule, beātīs

- Vōs coniungite!

- Carmina triumphī

- Ūnā canite;

- Chrīstō rēgī honor,

- Laudēs, glōria,

- Angelī hōc canent

- Saecla omnia.

Iam, puerī, silentiō factō, Gāius Iūlius Caesar nōbīs suam ōrātiōnem habēbit quam dē ambitiōne suā composuit. Hāc ōrātiōne fīnītā, Mārcus Tullius Cicerō suam habēbit. Ut prōnūntiātum est complūribus diēbus ante, hī duo puerī dē praemiō inter sē contendunt. Hōc diē fēlīcissimō duo clārissimī et honestissimī virī arbitrī sunt, Aulus Licinius Archiās et Pūblius Licinius Crassus. In rōstra, Gāī Iūlī Caesar, ēscende!

(Reads from a scroll or recites.) Mea cāra ambitiō est perītus dux mīlitum fierī. Bella multa et māgna cum gentibus omnibus nātiōnibusque orbis terrae gerere cupiō.

Bellum īnferre volō Germānīs et īnsulae Britanniae omnibusque populīs Galliae et cēterīs quī inimīcō animō in populum Rōmānum sunt. In prīmīs, in īnsulam Britanniam pervenīre cupiō, quae omnis ferē Rōmānīs est incōgnita, et cōgnoscere quanta sit māgnitūdō īnsulae.

Volō pontem in Rhēnō aedificāre et māgnum exercitum trādūcere ut metum illīs Germānīs quibus nostra parvula corpora contemptuī sunt iniciam. Ubi Rhēnum ego trānsierō, nōn diūtius glōriābuntur illī Germānī māgnitūdine suōrum corporum.

Vōs sententiam rogō, iūdicēs amplissimī, nōnne est haec ambitiō honesta?

Deinde rēs gestās meās perscrībam. Negōtium hūius historiae legendae puerīs dabō mentium exercendārum causā, nam mihi crēdite, commentāriī dē bellō Gallicō ūtilēs erunt ad ingenia acuenda puerōrum.

(Discipuli applaud.)

Nunc Mārcus nōbīs dē suā cārissimā ambitiōne loquētur. In rōstra ēscende, Mārce!

Quoad longissimē potest mēns mea respicere et ultimam memoriam recordārī, haec mea ambitiō fuit, ut mē ad scrībendī studium cōnferam, prīmum Rōmae, deinde in aliīs urbibus.

Ambitiō mea autem est omnibus antecellere ingenī meī glōriā, ut haec ōrātiō et facultās, quantacumque in mē sit, numquam amīcōrum perīculīs dēsit. Nōnne est haec ambitiō maximum incitāmentum labōrum?

Deinde, haec est mea ambitiō, ut cōnsul sim. Dē meō amōre glōriae vōbīs cōnfitēbor. Volō poētās reperīre quī ad glōriam meī cōnsulātūs celebrandam omne ingenium cōnferant. Nihil mē mūtum poterit dēlectāre, nihil tacitum. Quid enim, nōnne dēsīderant omnēs glōriam et fāmam? Quam multōs scrīptōrēs rērum suāram māgnus ille Alexander sēcum habuisse dīcitur! Itaque, ea verba quae prō meā cōnsuētūdine breviter simpliciterque dīxī, arbitrī, cōnfīdō probāta esse omnibus.

(Discipuli applaud.)

Ut vidētis, arbitrī clārissimī, puerī ānxiīs animīs vestrum dēcrētum exspectant. Quae cum ita sint, petō ā vōbīs, ut testimōnium laudis dētis.

Ambōs puerōs, magister, maximē laudamus, sed ūnus sōlus praemium habēre potest. Nōs nōn dēcernere possumus. Itaque dēcrēvimus ut hī puerī ambō inter sē sortiantur uter praemium obtineat. Servī, urnam prōferte! Nōmina in urnam iaciam. Quī habet nōmen quod prīmum ēdūcam, is vīctor erit. (Takes from the urn a small chip and reads the name Marcus Tullius Cicero.)

Tē, Mārce Cicerō, victōrem esse prōnūntiō. Sīc fāta dēcrēvērunt. Servī, corōnam ferte! (Places a wreath of leaves on the head of Marcus. The discipuli again applaud.)

(going up to Caesar)

Caesar, nōlī animō frangī. Nōn dubium est quīn tū meliōrem ōrātiōnem habuerīs.

(coolly) Dīs aliter vīsum est.

Vōs ambō, Gāī et Mārce, honōrī huic scholae estis. Utinam cēterī vōs imitentur. Aliud certāmen hūius modī mox habēbimus. Loquēmur dē-- (A knock is heard. Enter Gaius Licinius Crassus.)

Mī pater!

Mī fīlī! (They embrace.)

Māter mea mihi dīxit tē arbitrum in hōc certāmine hodiē esse. Tē diūtius exspectāre nōn potuī. Iam diū tē vidēre cupiō et ego quoque cupiō hōc certāmen audīre. Estne cōnfectum?

Cōnfectum est. Utinam hī puerī tē recitāre audiant! Tū eōs docēre possīs quōmodo discipulī Rhodiī in scholā recitent.

Ō arbiter, nōbīs grātissimum sit, sī tuum fīlium audīre possīmus.

(eagerly) Ō Crasse, recitā, recitā!

Sī vōbīs id placet, recitābō, meum tamen carmen longum est. Ēius titulus est "Poem of a Possum." (Recites with gesticulation.)

-

- The nox was lit by lūx of lūna,

- And 'twas a nox most opportūna

- To catch a possum or a coona;

- For nix was scattered o'er this mundus,

- A shallow nix, et nōn profundus.

- On sīc a nox, with canis ūnus,

- Two boys went out to hunt for coonus.

- Ūnus canis, duo puer,

- Numquam braver, numquam truer,

- Quam hoc trio quisquam fuit,

- If there was, I never knew it.

- The corpus of this bonus canis

- Was full as long as octō span is,

- But brevior legs had canis never

- Quam had hīc bonus dog et clever.

- Some used to say, in stultum iocum,

- Quod a field was too small locum

- For sīc a dog to make a turnus

- Circum self from stem to sternus.

- This bonus dog had one bad habit,

- Amābat much to chase a rabbit;

- Amābat plūs to catch a rattus,

- Amābat bene tree a cattus.

- But on this nixy moonlight night

- This old canis did just right,

- Numquam chased a starving rattus,

- Numquam treed a wretched cattus,

- But cucurrit on, intentus

- On the track and on the scentus,

- Till he treed a possum strongum

- In a hollow trunkum longum.

- Loud he barked in horrid bellum,

- Seemed on terrā vēnit hellum.

- Quickly ran uterque puer

- Mors of possum to secure.

- Cum venērunt, one began

- To chop away like quisque man;

- Soon the ax went through the trunkum,

- Soon he hit it all kerchunkum;

- Combat deepens; on, ye braves!

- Canis, puerī, et staves;

- As his powers nōn longius tarry,

- Possum potest nōn pūgnāre;

- On the nix his corpus lieth,

- Ad the Styx his spirit flieth,

- Joyful puerī, canis bonus

- Think him dead as any stonus.

- Now they seek their pater's domō,

- Feeling proud as any homō,

- Knowing, certē, they will blossom

- Into heroes, when with possum

- They arrive, narrābunt story,

- Plēnus blood et plēnior glory.

- Pompey, David, Samson, Caesar,

- Cyrus, Black Hawk, Shalmaneser!

- Tell me where est now the glōria,

- Where the honors of vīctōria?

- Cum ad domum nārrant story,

- Plēnus sanguine, tragic, gory,

- Pater praiseth, likewise māter,

- Wonders greatly younger frāter.

- Possum leave they on the mundus,

- Go themselves to sleep profundus,

- Somniant possums slain in battle

- Strong as ursae, large as cattle.

- When nox gives way to lūx of morning,

- Albam terram much adorning,

- Up they jump to see the varmen

- Of which this here is the carmen.

- Possum, lo, est resurrēctum!

- Ecce puerum dēiectum!

- Nōn relinquit track behind him,

- Et the puerī never find him;

- Cruel possum, bēstia vilest,

- How tū puerōs beguilest;

- Puerī think nōn plūs of Caesar,

- Go ad Orcum, Shalmaneser,

- Take your laurels, cum the honor,

- Since istud possum is a goner![5]

(Discipuli applaud.)

Omnēs quī Gāiō Crassō grātiās agere velint, surgite! (All stand.) Nunc, puerī, domum redīte.

(departing).

-

- Omne bene,

- Sine poenā

- Tempus est lūdendī;

- Vēnit hōra

- Absque morā

- Librōs dēpōnendī.

Valē, magister. Valē, magister.

A Roman Wedding

63 B.C.

Drāmatis Persōnae

- Tullia (Spōnsa)

- Mārcus Tullius Cicerō (Spōnsae Pater)

- Terentia (Spōnsae Māter)

- M. T. Cicerō Adulēscēns (Frāter)

- Gāius Pīsō (Spōnsus)

- Lūcius Pīso Frūgī (Spōnsī Pater)

- Uxor Pīsōnis (Spōnsī Māter)

- Flāmen Diālis

- Pontifex Maximus

- Iūris cōnsultus

- Quīntus Hortēnsius

- Prōnuba

- Sīgnātōrēs

- Tībīcinēs

- Līctōrēs

- Mārcipor (Servus)

- Philotīmus (Servus)

- Tīrō (Servus)

- Anna (Serva)

Scaena Prīma

Spōnsālia

Let the curtain be raised, showing a room furnished as nearly as possible like the atrium of a Roman house. A bench, covered with tapestry, on each side of the stage facilitates the seating of the guests. Cicero is heard practicing an oration behind the scenes.

Ō rem pūblicam miserābilem! Quā rē, Quirītēs, dubitātis? Ō dī immortālēs! Ubinam gentium sumus? In quā urbe vīvimus? Quam rem pūblicam habēmus? Vīvis, et vīvis nōn ad dēpōnendam sed ad cōnfīrmandam tuam audāciam.

(Enter Terentia. A slave, Anna, follows bringing a boy's toga, which she begins to sew, under Terentia's direction. Another slave, Marcipor, also follows.)

Nihil agis, nihil mōlīris, nihil cōgitās quod nōn ego nōn modo audiam, sed videam. Quae cum ita sint, Catilīna, ex urbe ēgredere; patent portae, proficīscere. Māgnō mē metū līberābis dum modo inter mē atque tē mūrus intersit. Quid est enim, Catilīna, quod tē iam in hāc urbe dēlectāre possit? Quamquam quid loquor? Tē ut ūlla rēs frangat?

(A crash, similar to that of falling china, is heard.)

Quid est? Vidē, Mārcipor!

(As Marcipor is about to leave, Philotimus enters at the right, bringing in his hands the pieces of a broken vase.)

Ō domina, ecce, dominus, dum ōrātiōnem meditātur, vās quod ipse tibi ē Graeciā attulit, manūs gestū dēmōlītus est.

(groaning) Lege, Philotīme, omnia fragmenta. (Exit Philomitus) Mihi, Mārcipor, fer cistam ex alabastrītā factam. (Exit Marcipor. To herself.) Tam molestum est ōrātōrī nūpsisse. (Covers her face with her hands, as if weeping.)

(proceeding with his practicing) Atque hōc quoque ā mē ūnō togātō factum est. Mārce Tullī, quid agis? Interfectum esse Lūcium Catilīnam iam prīdem oportēbat. Quid enim malī aut sceleris fingī aut cōgitārī potest quod ille nōn concēperit? Ō rem pūblicam fortūnātam, ō praeclāram laudem meī cōnsulātūs, sī ex vītā ille exierit! Vix feram sermōnēs hominum, sī id fēcerit. (Enter Marcipor with a small box.)

Hīc est, domina, cista tua.

(takes from her bosom a key and opens the box, taking out a package of letters, one of which she reads).

"Sine tē, ō mea Terentia cārissima, sum miserrimus. Utinam domī tēcum semper manērem. Quod cum nōn possit, ad mē cottīdiē litterās scrībe. Cūrā ut valeās et ita tibi persuādē, mihi tē cārius nihil esse nec umquam fuisse. Valē, mea Terentia, quam ego vidēre videor itaque dēbilitor lacrimīs. Cūrā, cūrā tē, mea Terentia. Etiam atque etiam valē."

Quondam litterās amantissimās scrīpsit; nunc epistolia frīgēscunt. Quondam vās mihi dedit, nunc vās mihi dēmōlītur; quondam fuit marītus, nunc est ōrātor. Tam molestum est mātrem familiās esse.

(Enter Cicero, from the right, followed by his slave Tiro, carrying a number of scrolls which he places upon a table.)

Quid est, Terentia? Quidnam lacrimās? Mihi dīc.

Rēs nūllast! Modo putābam quantum mūtātus ab illō Cicerōne quī mē in mātrimōnium dūxerit, sit Cicerō quem hodiē videō. Tum Terentiae aliqua ratiō habēbātur. Nunc vacat Cicerō librīs modo et ōrātiōnibus et Catilīnae. Nescīs quantum mē hūius negōtī taedeat! Nūllum tempus habēs ad cōnsultandum mēcum dē studiīs nostrī fīliolī. Magister dē eō haec hodiē rettulit. (Hands Cicero a scroll.) Mē pudet fīlī.

(reading to himself the report) Dīc meō fīliō, Mārcipor, ut ad mē veniat. (Exit Marcipor, who returns bringing young Marcus.)

Quid est, pater?

Tua māter, mī fīlī, animum ānxium ob hanc renūntiātiōnem dē tē habet. Mē quoque, cōnsulem Rōmānum, hūius renūntiātiōnis quibusdam partibus pudet. (Reads aloud.) "Bis absēns." Cūr, mī fīlī, ā scholā āfuistī?

Id nōn memoriā teneō.

Sunt multa quae memoriā nōn tenēs, sī ego dē hāc renūntiātiōne iūdicāre possum.

(continues reading) "Tardus deciēns!" Deciēns! Id est incrēdibile! Fīlius cōnsulis Rōmānī tardus deciēns! Māter tua id nōn patī dēbuit.

(angrily) Māter tua id nōn patī dēbuit! Immō vērō pater tuus id nōn patī debuit.

"Ars legendī A." Id quidem satis est. "Ars scrībendī D." D! Id quidem minimē satis est. Nūgātor dēfuit officiō! "Fīlius tuus dīcit scrīptūram tempus longius cōnsūmere. Dēbet sē in scrībendō multum exercēre, sī scrībere modō tolerābilī discere vult. Arithmētica A. Huic studiō operam dat. Dēclāmātiō A. Omnibus facile hōc studiō antecellit." Bene, mī fīlī. Ea pars hūius renūntiātiōnis mihi māgnopere placet. Ōrātor clārissimus ōlim eris.

Ūnus ōrātor apud nōs satis est.

Ōrātor erō ōlim nihilō minus. Facile est ōrātōrem fierī. Dēclāmātiō est facillima. Hodiē in scholā hanc dēclāmātiōnem didicī:

-

- Omnia tempus edāx dēpāscitur, omnia carpit,

- Omnia sēde movet, nīl sinit esse diū.

- Flūmina dēficiunt, profugum mare lītora siccant,

- Subsīdunt montēs et iuga celsa ruunt.

- Quid tam parva loquor? mōlēs pulcherrima caelī

- Ardēbit flammīs tōta repente suīs.

- Omnia mors poscit. Lēx est, nōn poena, perīre:

- Hīc aliquō mundus tempore nūllus erit.

Tālis dēclāmātiō est facilis. Audī quid dē geōmetriā tuā relātum sit. Geōmetria magis quam declāmātiō ostendit utrum tū mentem exerceās.

(continues reading) "Geōmetria D." Magister haec scripsit: "Fīlius tuus dīcit geōmetriam ōrātōribus inūtilem esse. Eī dīligenter domī labōrandum est." Ō Mārce, hōc est incrēdibile! Num dīxistī tū geōmetriam ōrātōribus inūtilem esse?

Ō, studium geōmetriae mihi odiōsum ingrātumque est! Omnēs puerōs istīus taedet. Tantī nōn est!

Etiam sī studium tū nōn amās, geōmetriam discere dēbēs. Tibi centum sēstertiōs dabō sī summam notam in geōmetriā proximō mēnse adeptus eris.

(grasping his father's hand) Amō tē, pater, convenit! Eam adipīscar!

(to Anna) Estne toga parāta?

Parāta est, domina.

Hūc venī, Mārce!

Ō māter, tempus perdere nōlō. Mālō legere.

Quid dīcis? Nōn vīs? Nōnne vīs novam togam habēre?

Nōlō. Novā mī nīl opus est. Tam fessus sum! (Picks up a scroll and is about to take a seat in the corner.)

Ad mātrem tuam, Mārce Cicerō, sine morā, accēde!

(Marcus is about to obey when a knock is heard at the door. Lucius Piso Frugi and Quintus Hortensius enter at the left.)

(greeting Quintus Hortensius) Ō amīcī, salvēte! ut valētis?

(greeting Lucius Piso) Dī duint vōbīs quaecumque optētis. Cicerōnī modo dīcēbam nōs diū vōs nōn vidēre, praesertim tē, Pīsō. Mārcipor, ubi est Tullia? Eī dīc ut hūc veniat.

Nōlī Tulliam vocāre. Nunc cum parentibus Tulliae agere volō, nōn cum Tulliā ipsā.

Nōn vīs nostram Tulliam vidēre! Quid, scīre volō?

Cum eā hōc tempore agere nōn cupiō. Id propter quod in vestram domum hodiē vēnī tuā, et Cicerōnis rēfert. Velim vōbīscum agere prō meō fīliō, Gāiō Pīsōne, quī fīliam tuam in mātrimōnium dūcere vult.

Meam fīliam in mātrimōnium dūcere! Mea Tulliola nōndum satis mātūra est ut nūbat. Mea fīlia mihi cārior vītā ipsā est. Eam āmittere... id nōn ferre possum. Ea lūx nostra est. Meā Tulliolā nihil umquam amābilius, nec longā vītā ac prope immortālitāte dīgnius vīdī. Nōndum annōs quattuordecim implēvit et iam ēius prūdentia est mīrābilis. Ut magistrōs amat! Quam intellegenter legit! Nōn possum verbīs exprimere quantō vulnere animō percutiar sī meam Tulliolam āmittam. Utinam penitus intellegerēs meōs sēnsūs, quanta vīs paternī sit amōris.

Tālia verba, Mārce Tullī, virī Rōmānī nōn propria sunt. Necesse est omnēs nostrās fīliās in mātrimōnium dēmus. Nihil aliud exspectā.

Nostra fīlia omnibus grātissima est. Semper enim lepida et līberālis est. Iam diū sciō nōs eam nōn semper retinēre posse.

Rēctē, rēctē! Meus fīlius bonus est; est ōrātor. Est quoque satis dīves. Rōmae duās aedēs habet; rūre māgnificentissima vīlla est eī. Cum illō fīlia tua fēlīx erit. Id mihi persuāsum habeō. Quae cum ita sint, Mārce Tullī, sine dōte tuam fīliam meō fīliō poscō.

Prohibeant dī immortālēs condiciōnem ēius modī. Cum mea fīlia in mātrimōnium danda sit, nēminem cōgnōvī quī illā dīgnior sit quam tuus fīlius ēgregius.

(shaking hands with Cicero) Ō Mārce, mī amīce, dī tē respiciant! Nunc mihi eundum est ut fīlium et sīgnātōrēs arcessam et iam hūc revertar.

(Exeunt Lucius Piso and Quintus Hortensius.)

Dīc, Mārcipor, servīs ut in culīnā vīnum, frūctūs, placentās parent. (Exit Marcipor.) Mārce, fīlī, sorōrem vocā.

-

- Tullia, ō Tullia,

- Soror mea bella,

- Amātōres tibi sunt

- Pīsō et Dolābella.

(Enter Tullia at the right.)

-

- Amatne Pīsō tē,

- Etiam Dolābella?

- Tullia, ō Tullia,

- Soror mea bella,

- Pīsōnem tuum marītum fac;

- Nōn grātus Dolābella.

Ō Mārce, tuī mē taedet. Quid est, māter?

Tullia, nōnne est Gāius Pīsō tibi grātissimus?

Ō, mihi satis placet. Cūr mē rogās, māter?

Rogō, mea fīlia, quod Pīsō tē in mātrimōnium dūcere vult. Tibi placetne hōc?

Mihi placet sī--

Sī--quid, mea fīlia?

Ō māter, nōlō nūbere. Sum fēlīx tēcum et patre et Mārcō. Vīxī tantum quattuordecim annōs. Puella diūtius esse volō, nōn māter familiās.

Pīsō dīves est. Pater tuus nōn māgnās dīvitiās nunc habet. Meum argentum quoque cōnsūmptum est. Etiam haec domus nostra nōn diūtius erit. Quid faciāmus sī tū nōn bene nūbēs?

Sciō patrem meum nōn māgnās possessiōnēs habēre; quid vērō, māter? Servīlia, Lūcullī spōnsa, quī modo rediit spoliīs Orientis onustus, semper suam fortūnam queritur. Misera Lūcullum ōdit ac dētestātur. Hesternō diē meīs auribus Servīliam haec verba dīcere audīvī: "Mē miseram! Īnfēlīcissimam vītam! Fēminam maestam! quid faciam? Mihi dēlēctus est marītus ōdiōsus. Nēmō rogāvit quī vir mihi maximē placeat. Coniugem novum ōderō, id certum est. Prae lacrimīs nōn iam loquī possum." Ō māter! ego sum aequē trīstis ac Servīlia. Nōlō Gāiō Pīsōnī nūbere. Nūllī hominī, neque Rōmānō neque peregrīnō, quem vīderim, nūbere volō.

Tullia, mea fīlia, mātris et nostrae domūs miserēre! Hodiē pater ā mē argentum postulābat quod eī dare nōn poteram. Pīsō dītissimus est et nōbīs auxiliō esse potest. Parentum tuōrum causā tē ōrō nē hunc ēgregium adulēscentem aspernēris.

Ō Servīliam et Tulliam, ambās miserās! Quid dīcis tū, mī pater? Vīs tū quoque mē in mātrimōnium dare?

Ō mea Tulliola, mē nōlī rogāre. Nescīs quantum ego tē amem. Sine tē vīvere nōn poterō. Id mihi persuāsum habeō. Putō tamen, sī pācem apud nōs habēre velīmus, tē mātris iussa sequī necesse esse.

Volō, mī pater, tē pācem habēre. Tua vīta tam perturbāta fuit. Nūbam, sed ō mē miseram!

(A knock is heard. Enter from the left Lucius Piso, Gaius Piso, and the signatores. They are greeted by Cicero and Terentia and seated by slaves.)

(as she receives them) Multum salvēte, ō amīcī. Tulliae vix persuādēre poteram, tamen nōn iam invīta est.

Bene, bene, hīc est mihi diēs grātissimus. Parāta sunt omnia?

Omnia parāta sunt, sed iūris cōnsultus nōndum vēnit.

Ille quidem ad tempus adesse pollicitus est.

Id spērō. Tībīcinēs, Mārcipor, hūc arcesse. (Enter Quintus Hortensius and his wife, together with the pronuba and the iuris consultus.) Salvēte, meī amīcī. Adsīdite sī placet.

Sī mihi veniam dabitis, nōn diū morārī velim. Īnstāns negōtium mē in forō flāgitat. Mihi mātūrandum est. (Goes to a table with M. Cicero and busies himself with the tabulae nuptiales.)

Mātūrēmus! Gāī et Tullia, ad mē venīte! (To Cicero) Spondēsne Tulliam, tuam fīliam, meō fīliō uxōrem darī?

Dī bene vertant! Spondeō.

Dī bene vertant!

(placing a ring on the fourth finger of Tullia's left hand) Hunc ānulum quī meum longum amōrem testētur aceipe. Manum, Tullia, tibi dō, et vim bracchiōrum et celeritātem pedum et glōriam meōrum patrum. Tē amō, pulchra puella. Tē ūnam semper amābō. Mihi es tū cārior omnibus quae in terrā caelōque sunt. Fēlīcēs semper sīmus!

Tabulae nūptiālēs sunt parātae et ecce condiciōnēs. (Reads) "Hōc diē, prīdiē Īdūs Aprīlēs, annō sescentēsimō nōnāgēsimō prīmō post Rōmam conditam, M. Tulliō Cicerōne Gāiō Antōniō cōnsulibus, ego M. Tullius Cicerō meam fīliam Tulliam Gāiō Calpurniō Lūcī fīliō Pīsōnī spondeō. Eam cum dōte dare spondeō. Ea dōs erit quīndecim mīlia sēstertium." (Turning to Gaius) Gāī Pīsō, spondēsne tē Tulliam semper amātūrum cultūrumque?

Id spondeō.

Spondēsne tū, Tullia, tē Gāiō Pīsōnī semper obsecutūram esse?

Id spondeō.

(stamping the tabulae with a seal) Nuc subscrībite! Tū prīmus, Cicerō, deinde Terentia et Tullia et Gāius.

(The tibicines play softly and the servi pass wine, dried fruit, and small cakes. Tullia, taking her glass of wine, steps forward and pours a little out as an offering to the gods. After the witnesses have signed in turn, the following words of congratulation are spoken.)

Beātī vīvātis, Pīsō et Tullia! Omnēs spōnsō et spōnsae salūtem propīnēmus! (All drink to the health of the betrothed.)

Sint dī semper volentēs propitiīque ipsīs domuī familiaeque. Sit vōbīs fortūna benīgna!

Tibi grātulor, Pīsō. Tū pulcherrimam et optimam puellam tōtīus Rōmae adeptus es.

Ō fortūnāte adulēscēns quī tālem puellam invēnerīs!

Sīgnāvēruntne omnēs? Tū, Quīnte Hortēnsī, nōndum subscrīpsistī.

Id statim faciam. (Signs)

Nunc omnēs cantēmus!

(All join in singing, accompanied by the tibicines.)

Scaena Secunda

Nūptiae

The house is adorned with wool, flowers, tapestry, and boughs.

The Pontifex Maximus (wearing a white fillet) and the Flamen Dialis enter from opposite sides, each preceded by a lictor with fasces, who remains standing at the side of the stage, while the priests pass on to the altar. The Flamen burns incense. A slave brings in a pigeon on a silver tray and hands it to the Flamen, while another hands to the Pontifex from a basket a plate of meal and one with crackers.

The priests, taking respectively the bird and the meal, hold them high above their heads and look up devoutly, after which the bridal party enters, from the left, in the following order:

The bride, preceded by the pronuba, comes first. Both take their places, standing at the right of the altar; next the groom, preceded by the boys, takes his stand near the bride, a little to the left; the guests follow and are seated.

Cicero hands wine to the priests, with which they sprinkle the sacrifices.

As the Flamen again looks up and raises his hands above his head, all kneel except the priests and lictors, while he pronounces the following solemn words:

Auspicia secunda sunt. Māgna grātia dīs immortālibus habenda est. Auspicia secunda sunt.

After all have risen, the pronuba, placing her hands upon the shoulder of the bride and groom, conducts them to the front of the altar. There she joins their hands and they walk around the altar twice, hand in hand, stopping in front when the ceremony proper begins.

Auspicia secunda sunt.

The Pontifex hands the groom a cracker, of which he partakes, passing it on to the bride. The pronuba puts back the veil, and after the bride has eaten the cracker she says to the groom:

Ubi tū Gāius, ego Gāia.

Both are then conducted by the pronuba to two chairs, placed side by side, at the right of the altar, covered with the skin of a sheep. They face the altar and the pronuba covers their heads with a large veil. (Place the same veil over both.)

(making an offering of meal to Jupiter)

-

- Iuppiter omnipotēns dīvum pater atque hominum rēx,

- Hōs spōnsōs bene respiciās, faveāsque per annōs.

- Iuppiter omnipotēns, precibus sī flecteris ūllīs

- Aspice eōs, hōc tantum, et sī pietāte merentur,

- Dā cursum vītae iūcundum et commoda sparge

- Multa manū plēnā; vīrēs validāsque per mensēs

- Hī habeant, puerōs pulchrōs fortēsque nepōtēs.

- Rēbus iūcundīs quibus adsīs Iuppiter semper.

-

- Iūnō quae incēdis dīvum rēgīna Iovisque

- Coniunx et soror, hōs spōnsōs servā atque tuēre.

- Sint et fēlīcēs, fortēs, pietāte suprēmī;

- Māgnā cum virtūte incēdant omnibus annīs,

- Semper fortūnātī, semper et usque beātī.

(The pronuba now uncovers the heads of the wedded pair and they receive congratulations.)

Beātī vīvātis, Gāī et Tullia!

Vōbīs sint dī semper faustī!

Vōbīs ambōbus grātulor. Sed nūlla rēs levis est mātrimōnium. Quid, Tullia?

Rēctē dīcis, frāter, mātrimōnium nōn in levī habendum est.

Sint omnēs diēs fēlīcēs aequē ac hīc diēs.

Spērō, meī amīcī, omnēs diēs vōbīs laetissimōs futūrōs esse.

(The curtain falls. The priests and lictors retire, all the rest, except Terentia and Tullia, keeping the same position for the next scene.)

Scaena Tertia

Dēductiō

The guests are sitting about the room. The bride is sitting on her mother's lap. Her wedding ornaments have been taken off and she is closely veiled. The groom takes her as if by force from her mother's arms.

Ō māter, māter, nōlō ā tē et patre meō discēdere. Ō, mē miseram!

Ī, fīlia, ī! Saepe tuōs parentēs et frātrem vīsere poteris. Necesse est nunc cum marītō eās.

Mihi, Tullia, cārior vītā es. Tē nōn pigēbit coniugem meam fierī. Id polliceor. Mēcum venī, Tullia cārissima!

Sīc estō. Prius mustāceum edendum est. (She cuts the wedding cake and all partake.)

Hōc mustāceum optimum est. Hōc fēcistīne tū, Tullia?

Nihil temporis habēbam quō mustāceum facerem. Multa mihi ūnō tempore agenda erant.

Tullia mustāceum facere potest sī spatium datur.

(taking another piece of cake) Tullia est dēliciae puellae. Sī ūnum modo mustāceum habēmus, ad novam domum Tulliae proficīscāmur.

Eāmus!

The curtain falls. A frame to represent the door of a Roman house is placed to the left of the stage; a small altar stands at the right: a circular piece of wood with holes bored in it as a receptacle for the torches (common wax candles) is placed on top of the altar used by the priests. The procession to the groom's house advances from the left in the following order:

The flute-players first, followed by a lad carrying a torch and vase; next the bride, supported on either side by a boy; the groom, throwing nuts to those in the street, walks at the side; a boy follows, carrying the bride's spindle; the others follow, two by two, all carrying torches and singing:

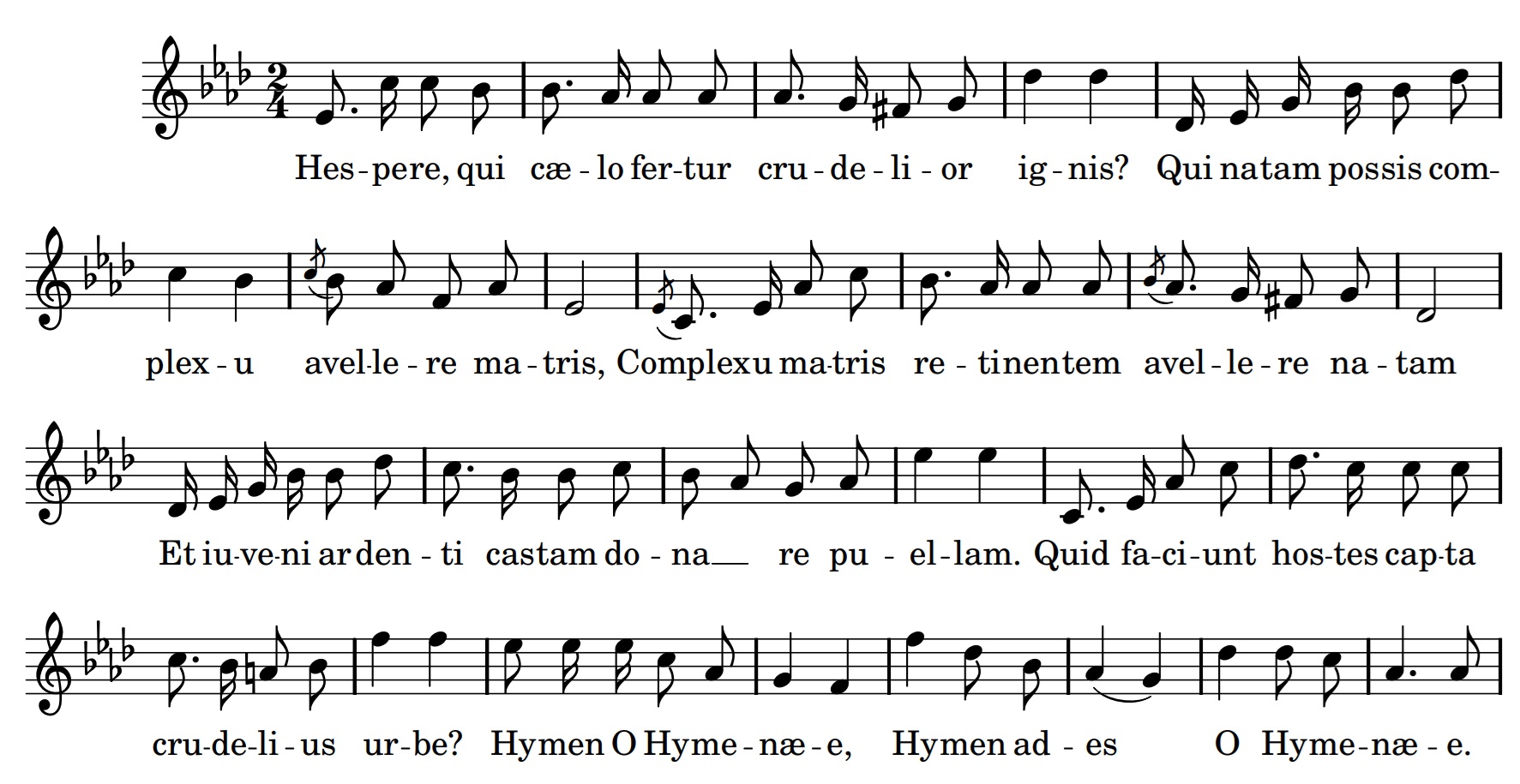

-

- Hespere, quī caelō fertur crūdēlior īgnis?

- Quī nātam possīs complexū āvellere mātris,

- Complexū mātris retinentem āvellere nātam

- Et iuvenī ārdentī castam dōnāre puellam.

- Quid faciunt hostēs captā crūdēlius urbe?

- Hȳmēn ō Hymenaee, Hȳmēn ades ō Hymenaee.

When the groom's house is reached, the bride winds the door posts with woolen bands and anoints them with oil to signify health and plenty. She is then lifted over the threshold by two boys to prevent possible stumbling. The groom, Cicero, Terentia, Lucius Piso and his wife, enter the house and place their torches on the altar; the others remain standing outside. All continue singing, accompanied by the flute-players, until after the groom hands to the bride a dish, on which incense is burning, and a bowl of water, which both touch in token of mutual purity, and Tullia again repeats the words:

Ubi tū Gāius, ego Gāia.

(presenting to her the keys, which she fastens in her girdle) Sit fēlīx nostra vīta! Clāvēs meae domūs, mea uxor, accipe!

Tullia kindles the fire on the altar with her torch, and then throws it to a girl outside. The girl who catches the torch exclaims:

Ō, mē fēlicissimam! Proxima Tulliae nūbam.

(Tullia kneels at the altar and offers prayer to Juno.)

-

- Iūnō, es auctor mūnerum,

- Iūnō, māter omnium,

- Nōbīs dā nunc gaudium.

- Iūnō, adiūtrīx es hominum,

- Iūnō, summa caelitum,

- Nōbis sīs auxilium.

Fīnis

"Four or five of these (walnuts) are piled pyramidally together, when the players, withdrawing to a short distance, pitch another walnut at them, and he who succeeds in striking and dispersing the heap wins." Story, "Roba di Roma," p. 128.

See Johnston, "Private Life of the Romans," p. 81; or Miller, "The Story of a Roman Boy."

Here, as well as elsewhere, remember that Gāius and Gāia are each three syllables.

Tune of "Onward, Christian Soldiers." Slightly altered from Education, Vol. IX, p. 187. The author hopes that this most obvious anachronism will be pardoned on the ground that this hymn appeals to young pupils more than most Latin songs, and is therefore enjoyed by them and more easily learned.

Anonymous